During one of my hospice volunteer trainings a nurse spoke to us about her husband’s illness and eventual death. She said his death was peaceful and quite beautiful, especially after the long struggle with cancer, but then, she said, “The grief that followed was a real kick in the teeth.” I had never thought about death and grief as two separate experiences. And I think that much of what troubles me around death is actually the depth of grief that I could/will feel. While this is a project on mortality, I want to explore grief, to give it some real consideration. I sat down to speak with a grief counselor.

I would be grateful to hear your thoughts on grief. Death and grief are obviously linked, but they are quite separate also, right?

It’s true. Death and grief are linked but they’re separate events and ways of feeling. The last death that I personally experienced was my daughter-in-law’s. Jaimie died this past January, a couple of years after the death of my son. Her death was peaceful. She had been dying for a long, long time. After my son, her husband, JK, died, she rallied…I don’t know how…it was extraordinary. But finally she was ready to die, she talked about it, she made peace with the boys, she has three sons…had three sons.

Was she ill?

Yes. She had metastatic breast cancer. Jaimie knew she was dying. She knew it would never go away. The boys knew. They were ten, twelve and fourteen. The death…there were tons of friends around. Her mom was there, I was there. She died peacefully. She died really peacefully. She was at home. She was on hospice. But it was…. I mean I had two sons die, my mother died, and my aunt who I lived with in high school…they all died within a short time-frame just before Jaimie. But Jaimie’s was really a culmination…it just put me into a very dark place. Not dark in terms of…just…like a cocoon. I was just WRAPPED and moving through my days. And I knew it. I’d been there before. But all these deaths kind of wrapped me. About three weeks ago, I did my sitting (meditation), and it just…this veil dropped away and I felt the light coming in. It was lighter. It was like, life was bright! Now it’s been six years since my son Jason died, two and a half years since JK died, and two days before that my mother died, and a month after that my aunt died. And Jaimie died in January. That’s how long it can take for the grief to…it’s like this and this… (gestures ‘grasping at nothing’)…and you can’t really follow it always. And sometimes it’s important to detach just for your own health…but then it’s important to be aware of that detachment.

That’s a lot of close deaths in just six years. Would you be willing to tell me a bit more about them, individually?

The two sudden deaths, my two boys, were not peaceful. The doctor worked on Jason for over an hour to bring him…to try to start his heart. Jason had just operated at the hospital and then he’d gone to work out and collapsed suddenly. And my other son, JK, was hit by a car. He went straight up in the air and came down on his head and died. Those sudden deaths are, for those who are left…. I was in shock and stayed in shock for I don’t know how many years after Jason died and then when JK died…it IS the cocoon. And Jamie’s death darkened the cocoon. But I believe that it’s sort of a womb-like area that holds us, nurtures us, supports us. And I think that’s what shock is and I think that’s what many people call depression is. It’s a moist, damp area that lets us process and grow. It opens the seed of life and awareness again to other possibilities. But sometimes it takes a long time for that seed to germinate and grow. Sometimes the outer part of the seed is a little thicker and more dense. It can work. That’s how it worked for me. It gave me an awareness of grief around sudden death. Then my mother, who was 94 and not really sick but she had some respiratory problems, she died peacefully, and my aunt died peacefully, and Jaimie did. But they’re all different and I don’t think you can mourn collectively. I think one arises and the memories are there and they can intertwine but there’s one primary person to mourn and then that person goes back into dormancy and then another arises. They come and go.

It’s not possible to mourn as a general concept, you mean? We mourn specifically?

Yes. You mourn a person. You mourn individuals rather than a collective death. That doesn’t mean you can’t be aware of them at one time…we can be aware of war and atrocities…but to mourn someone and to grieve the loss of someone, there has to be A SOMEONE.

Would you define grief, mourning and bereavement?

Mourning is the outward expression of grief.

And grief is defined as deep distress or sorrow over a loss. So it’s the process of reacting to a loss?

Exactly. And bereavement is more of a clinical term. Bereavement is the time that you go through after someone dies. I am a Bereavement Counselor that means I deal with people who are left after someone dies…or after a loss actually. Someone recently described an interesting thing that I never really thought about before. She was a caregiver for her parents, full-time for the last two years. Her parents died this year within two weeks of each other. She said the loss of her extended family has really been hard for her. She said, “All the doctors, the nurses, the aides, the health practitioner, the nurse practitioner…” she goes through this litany of people who attended to her parents, people she saw frequently, who came to their home…she said that now, “It’s excruciating. I am all alone. I had all of these people and I have none of them anymore.” I’d never really thought about that as being an extended family and a huge loss for people. Especially for people who’ve had care for a long time. For their caregiver, after it’s over, not only are they no longer caring for the person who was sick and that’s a loss, that’s a primary loss, but this whole life, this whole life-style is gone. This woman cried. She said, “I didn’t think about it until it wasn’t there.”

We grieve the loss of people we love and we grieve for pets, but does grief extend to the loss of memories and future hopes that are no longer possible? It seems it could just keep going and going deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole.

It does. That’s why to pathologize things like someone having a conversation with the person who died, or to pathologize, “I felt him in bed with me, I touched his hand,” though ‘he’ had died months earlier, is really a disservice. First of all, we don‘t know. We don’t know what happens after death. We can surmise or we have belief systems around that, but to pathologize this period of mourning and the grief that we feel is to minimize what someone is going through. If it gives comfort and some support and it has meaning to someone, I think it’s a valuable tool for them to use to become present in this “new” life. That’s why when someone dies you don’t go to a traditional therapist because there are things that people go through over time that are unique to grieving. Grief is different. That is part of why I explained to you my whole experience, because yes, I do go to a therapist, yes I do go to group meetings and I have a sangha, a community of people who meditate. I am living my life. But I am also processing the deaths, having the memories stay present with me and arise into my conscious awareness. It took me a long time to balance all of that. Was I sick? No. I was in grief. I did my work, I had my relationships with family and friends, but I also am dealing with my grief in whatever way that I do. And it’s very individual. So it did take…it has taken…it will never really leave. So, back to your question… (laughs)…yeah, everything filters down. It changes. I had a conversation with somebody yesterday about the issue of loss and she said, “You go through all of this and no matter what the death, you are changed forever.” So that’s really the bottom line. You’re changed.

I love the image you invoked earlier of the cocoon because while it evokes a very real feeling of being tightly wrapped and isolated or enclosed, a cocoon is also so nurturing and transformative. It’s quite complex.

I picked this piece of paper up off the floor yesterday and I thought, “Oh my gosh! I forgot I wrote this!” and it says: “Grow. Change. Renew.” I thought of that when you were reminding me about the cocoon, that the person or creature inside the cocoon grows and changes and actually renews. You actually become NEW.

What do you think it is about loss and permanence/impermanence that we wrestle with and often find so difficult or scary?

The only thing that I think is permanent is impermanence. Our body is shedding cells constantly. The air around us changes constantly. I walk to work in the morning and I watch the flowers bloom in the early spring and then those die and the petals fall onto the soil and then they become part of the soil…then seeds start growing…it’s a good reminder…this is the microcosm of all life; it comes and it goes. And if we can sit with that and just be real about that, that things come and go, it becomes less scary.

Thinking about my own death impacts me, emotionally, much less than thinking about the eventual deaths of the people I love, who I may outlive. There’s coming to terms with my own death, but the more difficult one for me is about not being able to control things and keep those I love safe.

We had a meeting the other day and somebody was saying that we have to be really careful when we go to some of the Projects and to take an escort if you’re going to go. …(laughs)…And I said, “Jason was coming from working at a hospital, he went next door, he worked out, he walks up ten stairs, and he dies. JK walks out of a football game, he’s an anchor for Channel Two, the photographer walks across the road, JK takes one step onto the road and gets hit by a car.” I said, “After these things, why would I worry? I have no way of determining what’s going to happen in the next instant!” For me, it’s taken years, but you know what? You can go with an escort or without one, you can do whatever you want in the Projects or wherever and you will live to be one-hundred-six and you’ll be fine, or you will die. Is that being fatalistic or nihilistic? I don’t know. But I’m just not going to worry about it because I can’t do anything about it. I can encourage kids to go to school. I can be supportive to people. But in terms of life and death? I’m not it. I know it would be nice to think that I’m the determining factor about everybody’s life and death, but the truth of the matter is, I’m not. I promise you I can’t keep you alive. So I don’t know. I don’t have that anymore. Since the boys died, I’m just…I’m not going to protect anyone from anything because it doesn’t…you can’t… I hear what you’re saying, I mean I don’t want any more of my kids to die, I’m not saying that, I’m saying I can’t prevent it.

Do you know what motivated or helped you move forward after Jason’s death and then all of the subsequent deaths you experienced?

That’s an interesting question. I’ve wondered that myself, actually. One answer that I came to over time is that I’m really grateful for my parents. My mother…I don’t remember a time when the glass wasn’t half full. Everything was light! You could look at something one way but she could always see the goodness of it. And my dad was similar. He laughed easily. He was a little silly. And they both liked each other. There was real genuineness in them. And no matter what happened, life was full to them. It was full until Dad died. And then after, Mother had a full life. She went places with friends. I mean, they did everything together, Mother and Dad did. But she clicked right into, “Okay! That was that part of my life, now here’s this next part!”

How old was she when your dad died?

She was seventy-eight. Mother was real flexible. I really did look at, “What is it that allows me to continue and not sink into…something?” I think that is a big piece: I had good modeling. And the other, is that I’m very responsible for my own modeling to my own children. So rather than give them a lot of blah, blah, blah, I model that. I’m not negating my own need to find my own way through this, but there is part of me that says, “Get up and do this! Because you are that person for them. How you saw your parents, they are going to see you. So you need to buck up!” And I don’t mean get out of the grief. I mean, just go to work…

…And DO the grief.

Yes. Do the grief and keep their memories alive and talk about them. Those are the things I use and my kids use to go through the grieving process: a lot of humor, a lot of talking about things.

How old were your sons when they died?

Jason was thirty-seven, he died in 2008 and JK died in 2011. He was forty-one.

Can you tell me about your journey to becoming a grief counselor?

I started volunteering in Las Vegas, at Nathan Adelson Hospice. They gave me some groups…this was one year after Jason died. That’s the time-frame required for volunteering if you’ve experienced a close death. I was working at the university (of Nevada) and Nathan Adelson was right next door. When I moved back to New York I started volunteering at VNS (Visiting Nurse Service) and then I applied for this position, Bereavement Counselor. It’s been four and a half years since I’ve been doing this specific work. I developed a program in the last year called Mindfulness-based Grief Reduction that’s based on the sixteen Mindfulness breathing exercises, activities, some writings and things like that. It provides tools for people to remain somehow coherent in terms of their energy and their focus during the time that they’re grieving in the most intense way. People are looking for ways to find some quietness around the memories and to be okay with the memories. So that’s what I’m doing: putting what I’ve found to be useful tools for myself into a program that I can offer to other people.

Would you say that Jason’s death brought you quite specifically onto this path, working with bereavement, or were you doing work like this before?

My research, up to that time, was about energy fields. Most of it was with infants and young children. We were measuring the frequencies of different people, at different times, over time. One was through the Child and Family Research Center at the University of Nevada. Then in Arizona there was a group that works with teens. We measured the frequencies of their energy before and after their meditation, before and after their movement activities…so I was interested in how energy changed and how we had the capacity to change it and bring it into coherence and harmony ourselves; to do that is our job, not someone else’s. All of this work fed into looking at death and dying.

You mentioned earlier the value of having good modeling from your parents, maybe particularly, your mother. I think it’s so important to have models for how to…do anything, really! There are cultures where grief is a much more public, much more communal experience. What are your thoughts on the benefit of that, or not, and the challenge, perhaps, in our culture, especially now-a-days where everything is so private and hidden?

When I was little, we lived in a neighborhood that was Irish Catholic, mostly. Not all, but mostly.

Where did you grow up?

In Wisconsin. And in this neighborhood, there were a lot of older people…. We moved from that neighborhood when I was five, so these are memories from when I was very young. When somebody died, my brother and I would go, “Ha!”…(big smile and expression of excitement…laughs)…we knew it would be a party and we knew there’d be food. A couple of times the bodies were laid out on the dining room table or somewhere in the home…this is probably also another facet of why I’m not totally encapsulated with this idea of death being horrible. We would eat, it was party, people were nice, people laughed, we could play…all the kids went to all the funerals! …(laughs)… It was great! Somebody died, it was a good thing! We’d have the BEST food. My mother was very much about vegetables. Grandpa had a garden and we’d go pick all our vegetables and she’d cook them so we didn’t have any crappy food EVER. So if you could have cake and cupcakes and candy at these funerals it was like, “Oh my gosh!” So my initiation with death was good. I remember this one house, there were two elderly sisters and a brother who lived there. I remember that the brother, Johnny, died. He was in his eighties and was always very nice to us. People would walk everywhere and he’d always stop and say, “Hi.” So it wasn’t like I didn’t know him and he just happened to die and there was food. We knew him, and it was part of what we knew: death happens; people are born and people die. So we’d go to these funerals and people would cry, but they’d also laugh. It was a whole mix. I do think there needs to be a more public expression of camaraderie and support. When people come together around a death, it changes the whole idea of death. But that’s me. A couple of my kids really have…like, “Really? We’re gonna do a funeral??” And then I have to go through the whole, “This is what it’s about, this is why we do this,” and they’re in their forties. They’re not six years old. So people have a different awareness of it, maybe particularly in this culture. The funerals for the boys were massive. One was held at the university gym. It was huge. And some of my kids were reticent about that. About the whole thing. But I think it was helpful in their own grief process. I really do. I think it was vital. But I don’t know that they think that. It’s interesting how people see it differently but I personally think it’s important to have a funeral, big or small, just to have people come, and be around. Humor is so important! And when people come together they can remember the goofy times. They can remember the funny stuff that happened. You don’t get to do that by yourself. You’re not gonna sit and laugh by yourself. I mean I might …(laughs)… but most people don’t. Also, when you have an influx of people at the funeral, some of those people are going to show up after and you then have this ongoing support.

How has your relationship with grief and mortality changed in these last six years?

It’s evolved. Absolutely. Mortality…sometimes I think that in many ways it must be welcoming and that we’re taught to not have it be welcoming. I don’t mean suicide, I mean just thinking about the change and to be curious about it. I’ve always been curious and it’s just one more thing to be curious about. Grief has evolved to a peacefulness over these years. I can be peaceful in a violent death and peaceful in a non-violent death. And I think it’s because I’m really quiet about control. I don’t have it. I can see “it” as it is. The reality is that “it” is. It just is. So I can leave it as it is. Oftentimes I tell people, “That is the way it is, so let’s just be with what IS instead of what we’d like it to be.” So that’s my lesson I’ve learned.

That’s huge!

Yeah, it is huge. It’s ongoing, of course. It’s about pulling it back for me to remember, not just giving it to other people, but to remind myself. It’s even as small as sometimes here at work we can’t find an office to see people. We’re running around madly to try to find any empty office, and it just is. It’s not someone’s idea of a joke. It’s a neutral situation and it’s how I see it or how I deal with it that gives it any heat or any meaning. The more I’m aware of that, the more life is just one step and then another.

When you’re counseling people through grief, is there a common struggle that people have?

There is one, maybe specific to hospice, which is what I do. There were some researchers from Cornell here the other day talking about the massive increase in the use of Oxycodone. Families are asking for it because of the fear of morphine. Morphine has such a negative connotation, opium dens etc.. People have this idea of it, that it kills. That it stops the heart. It’s a pain drug that apparently has less side-effects than most. Oxycodone has HUGE side effects compared to morphine. And it’s not as regulated. My answer to your question, after this preamble, is that I believe that one of the hardest things is when people latch onto guilt. Morphine is one of THE biggest things to get past. “If I hadn’t let them give her morphine, she wouldn’t have died…she would’ve lived another week….” The guilt is overwhelming for people because they can’t do anything about it. They can never, ever, redo it. And they can’t really re-frame it because that was that! I’ve had nurses come in to talk to a bereavement client about morphine but they just can’t get past it. That is a tough one for people.

What is important to understand about grief?

One thing about grief is that you really have to attend to it. You have to be present with your sense of loss. Even if you didn’t like the person who died, your life changes and so the loss is meaningful. It’s also okay to be okay with the death. You don’t have to have specific feelings about it. You just have to be present with whatever feelings arise. They come and they will go. To attach to the guilt keeps guilt there and allows it to build and get denser and denser and it becomes like the hulk…like this monster that envelops you. So be present with the feelings and let them come and let them go. Because they will! If a pilot takes his or her hands off the controls for a moment and lets the plane fly, the plane will fly. They’re built to fly. If you want to keep the energy moving, keep your hands off it. Don’t try to make yourself guilty because you think you should be. Let the guilt be there, if it is, but let it flow through you and let it go. Let the anguish, let the sadness, let the anger come, but let it go. So it’s like taking your hands off but keeping your awareness there until it starts fading. “Ah, my little anxiety, I see you’re here! Welcome!” and then you see it go. And it doesn’t mean that it won’t come back, but at least you have a method. And it doesn’t mean those feelings are there for just a second, I’m not saying that, but as long as they are there, be aware of them, “You’re still here! This is a long visit!” It’s helpful to really personify the feeling so that it’s not getting stuffed down in you because it will arise again, with great vigor!

Thank you so much! This has been very informative for me and I think will be helpful to people…at some point all of us will likely have to deal with grief and a cocoon of our own. I really appreciate your time and you sharing your story and incredible insight. Thank you so much.

Thank YOU so much!

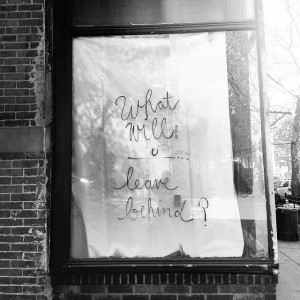

Photo Credit: Aussiegall, Flickr.com

Thank you for reading this interview! I look forward to your thoughts.